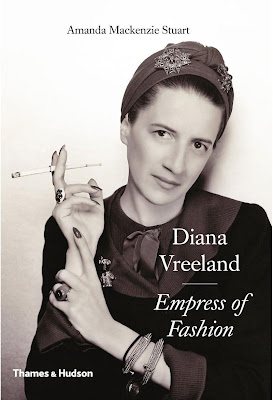

I devoured the new Diana Vreeland biography, Empress of Fashion by Amanda Mackenzie Stuart. I've read DV and The Eye Has to Travel and watched the DVD of the same name. I'd looked at her gorgeous magazine features and covers. I loved them but felt they were all telling the same story, reading from the same script that Diana herself had written. This new biography digs a bit deeper to create a thoughtful portrait which looks beneath the dazzling surface of its fascinating subject matter, the woman who Cecil Beaton described as, "one of the most remarkable creatures who has lived and worked in the zany confines of the fashion world".

Myths abound about Diana and Diana was behind most of them. There's the story, for example, that Carmel Snow saw her out dancing and offered her the job at Harper's Bazaar. Mackenzie Stuart shows how Snow would have known her already and that, in fact, she was already working for another Hearst title, Town & Country. But, although this book does do a fair bit of myth-busting, it's not done unkindly. Diana has been criticised and satirised for her sometimes tentative grip on the truth. While Mackenzie Stuart acknowledges this, she holds up Diana's imagination and inventiveness, which is so suited to the world of creating fashion fantasies, as born an effective survival tactic during an unhappy childhood.

Mr and Mrs Reed Vreeland, as shown in Vogue 1931. Reproduced in The Thirties in Vogue.

The book delves into her childhood and, specifically, her troubled relationship with her mother. There are some remarkable extracts from Diana's journals which seem to carry through to her adult life. She vows to become a popular girl, the popular girl - "the girl" - and her entries indicate the dogged determination with which she pursues this aim. And it worked. Her official "coming out" to society was deemed to be a great success and - even more successful by the standards of the time - was that she captured a handsome husband, Thomas Reed Vreeland. Though living in a fabulous social whirl by anyone's standards, it's interesting how Diana applied the same energy and discipline to establishing her place within society: she seems to have picked out certain woman to observe, admire and, to a degree, ape: the interior designer Elsie de Wolfe and Chanel, who she particularly admired for her skills in the "art of living".

(via)

Initially hired by Harper's Bazaar as a stylish representative of international set and to form a link between society, the magazine and its readers, her contribution grew to be much more than this, becoming a recognisable face and voice for the magazine. Her "Why Don't You?" column, equally parodied and praised, first ran in 1936. Really Diana's plea to inject more fantasy and beauty into everyday living through absurdly extravagant suggestions, it was never intended to be taken seriously. "Why Don't You install a private staircase from your bedroom to the library with a needlework carpet with notes of music worked on each step — the whole spelling out your favourite tune?", one read.

(via)

As I mentioned before, I found one of the most fascinating aspects of this book to be finding out what Diana did in the 1940s. Carmel Snow - partly due to astuteness partly to want to keep the Paris collections to herself, I suspect - charged Diana with being a catalyst for change in the American fashion industry and giving it some of her famous "pizzazz". The Second World War increased the need for this focus. The General Limitation Order L-85 restricted the amount of fabric which could be used in a garment (like the Utility scheme in Britain) actually made for styles perfectly suited to the US sportswear style. Mackenzie Stuart shows how the practical "popover", as shown above in the collection of Met Museum, was conceived by Diana but realised by Claire McCardell. It was the garment that made McCardell's name as a designer and was mass-produced and low-priced and, unusually for such a cheap garment, splashed all over the pages of Harper's.

It wasn't just with designers with which she forged close relationships in this period (successful collaborations seem to be a trademark of Diana's whole career). Diana also worked with photographers like Louise Dahl-Wolfe to create a new image of America, with dramatic images of the landscape reinforcing the designs and the birth of the glowing with health, all-American girl.

Diana Vreeland, as depicted by Cecil Beaton in The Glass of Fashion

The idea of the "girl" crops up again and again in this book: Diana's desire to be "the girl" and to inspire the readers to be "the girl", or the fact she never bothered learning the name of her put-upon assistants, simply screaming "girl" at them (no definitive article for these poor harassed women). The book also quotes from the article which gives this blog its name, published in 1947 during Diana's time at Harper's, and urging the reader to move with the latest shifts in fashion, "if you're not a Last-Year Girl". That shift was, of course, Dior's New Look, which put Diana's efforts and fashionable American women back in their place for a bit.

But only for a bit. Diana was poached by Vogue where her impact has been better documented and she eagerly promoted new American faces, like Barbra Streisand and Lauren Hutton, as well as new ideas, like the British youthquake. You get the impression that the 1960s suited her energy and her appetite for dressing-up and reinvention.

Once the world of fashion shifted again, however, she found herself adrift, her fantasies not sitting so well with the needs and wishes of a new generation of working women. In 1971 she was asked by New York's Metropolitan Museum to be a consultant to their fashion and costume shows. Working within a museum and seeing the amount of curatorial expertise and care which goes into each exhibition, I can only imagine the frustrations of her fellow workers in trying to scale down the fantasy and up the level of historical accuracy. And, of course her shows were blockbusters, adored by the public.

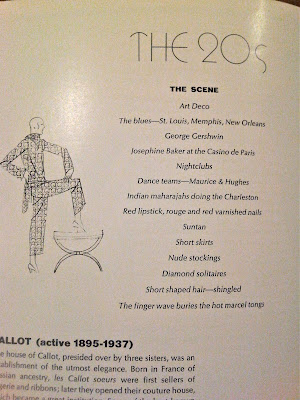

The subjects for her shows were favourite Diana themes: Hollywood, Russia, the Jazz Age. The above scan is taken from my copy of the leaflet produced for her 1910s, 1920s, 1930s: Inventive Clothes show, which reads like an evocative piece of fashion editorial, rather than a museum-produced document.

It goes without saying that this biography is a must-read if you are interested in fashion in the twentieth-century. Bringing together so many strands and different ideas, it's impossible not to read it without feeling inspired yourself. While Diana sometimes appears naive to the point of self-destructiveness, it's impossible to read this without admiring her energy, and her dedication to the pursuit of beauty.

Diana Vreeland has been quoted as saying very many witty, silly and/or astute things. My favourite, however, is this one which seems to sum her philosophy up perfectly: "What have we got in life? Love, friendship, work, guts, and all these delicious tiny fragments that can be the most attractive things in the world."

I love this review. I've been meaning to read this one, and now I simply have to get it.

ReplyDeleteThe Cecil Beaton drawing forced me to pull out my copy of the Glass of Fashion and reread his comments about Mrs. Vreeland. So fascinating!

Thank you. I really recommend it - it sends you off in hundreds of different directions wanting to find out more, always a good thing in a book I think!

Delete